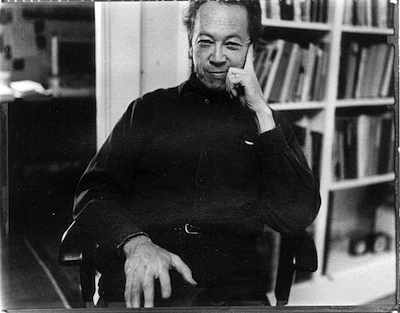

An introduction to Lowry Pei, author of the novel Over the Fence (TheWriteDeal.org). Pei’s first book, Family Resemblances, was published by Random House in 1986. His stories have appeared in Best American Short Stories 1984, The American Story: The Best of StoryQuarterly, and his book reviews have been published in the New York Times Book Review. Pei’s unique point of view owes much to his unlikely origins as the son of an engineer from Suzhou, China, and a schoolteacher from a small town in Kansas. He lives in Massachusetts with his wife, and teaches writing at Simmons College.

Quick Facts on Lowry Pei

- Lowry Pei’s website

- Home: Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Comfort food: linguine with clam sauce

- Top reads: Eudora Welty, The Golden Apples; Walker Percy, The Moviegoer; Charles Dickens, Bleak House; Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own; Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men.

- Current reads: Queen of America by Luis Alberto Urrea

What are you working on at the moment?

Since the beginning of the school year, I’ve mostly been writing comments on my students’ work. I taught two creative nonfiction classes in the fall, and I’m teaching a fiction class, and a writing pedagogy class, this spring. I wrote about 55,000 words of comments last semester, which is not unusual for me. I was trying to write an essay on the difference between encountering a text on paper and reading it on a screen, but nearly everything I said about this turned out, on second reading, to be obvious. Still, there’s something that needs to be said about the thingness of a text, now that it can no longer be taken for granted.

Somewhere in the back of my mind, a story I wrote about a year ago is thinking about becoming a novel.

Where did the idea for your novel Over the Fence come from?

Over the Fence came from an image that stuck in my mind and wouldn’t stop recurring. In it, I seemed to be standing in the backyard of the house in St. Louis where I grew up, looking at the back fence with weedy vines on it, an ornamental plum tree that grew there, and the brick-paved alley that ran behind the fence. Nothing special was happening in this scene; it was daytime, quiet, no one around. It was the most ordinary image in the world, but it kept occurring to me. A story often starts for me as an image that won’t go away; it seems to me that the image is alive, is an awareness. While I am looking at it, it is looking back at me. The story, somehow, is in the image. As Joan Didion said, “N.B.: You don’t tell it, it tells you.”

“A story often starts for me

as an image that won’t go away.”

A transformed version of the image occurs at the end of chapter 5 of the novel, but in a larger sense the novel literally involves digging into this image, as Lucas digs a giant hole in his backyard and stumbles upon a way to get into a spirit world.

What do you hope readers will take away from your work?

I was thinking about that pretty hard when I was revising this novel, and in the end I came to this: I want readers to take seriously their duty to their secret self.

I think about a novel thematically at the end of the process, not at the beginning. When I thought about Over the Fence this way, I realized I was saying that there are two very different things that go by the name of love: desire plus power, and desire plus trust. It matters a great deal not to mistake one for the other.

Who do you picture as the ideal reader of your work?

One thing I’m sure of is that my books are not written for a moralistic reader, or for one who is constantly passing judgment. In this novel in particular, I’m writing for readers who are willing to let the unexpected and unrealistic coexist in their imagination with the most everyday kind of reality, readers who like to take the risk of believing something that’s hard to believe. From early on in Over the Fence, I wrote knowing that to some people it would look like the silliest damn thing they ever read. But I couldn’t let myself be stopped by that. I could only write for readers who are willing to climb downward into the deeper layers of the self.

My ideal reader is at home with loss, and remembers what it’s like to have a hope that admits of no compromise.

My ideal reader deeply loves ordinary day-to-day life, is not bored with it, is not blasé.

I think for the ideal reader, reading is a secret assignation with the self.

Where and when do you prefer to write?

In my writing shed in Prince Edward Island, Canada, in the summer. In my shed there’s no internet and no phone, and outside is a meadow that ends at the shore. It can’t be beat.

I need to know that I can look forward to a large block of time with few interruptions or obligations, a time when I can live inside the world of my creation for hours every day. Once I get going, I can write for most of the day, with breaks for naps and lunch, day after day. I can’t write a novel by working an hour a day; the writing is no good and I just end up frustrated.

Where would you most want to live and write?

I couldn’t live in Prince Edward Island year-round, even if we had a place that was winterized; the winter would be too long and too isolating. I think I would stay right where I am, in Cambridge.

Do you listen to anything while you work?

Nothing except the ambient sounds of the outside world. I need quiet so I can hear what the voice in my head is saying.

Do you have a philosophy for how and why you write?

I think writing is something you do because, for some reason, you have to. Writing is self-causing.

Mario Vargas Llosa, in Letters to a Young Novelist, says “dissent from real life, from the world as it is . . . is the root of the novelist’s vocation.” And this: “Authenticity or sincerity is for the novelist: the acceptance of his own demons and the decision to serve them as well as possible.” I think that’s what I have done.

I do my best to follow Ray Bradbury’s two-word piece of advice: “Don’t think.” For me, the imagination always does something other, never what it is told. There is no point in trying to tell it what to do. My job when I’m writing a first draft—and I have to remind myself of this every day that I write—is to listen to the little voice in my head and write down what it says. The thinking, and there’s a great deal of it, should come later, during revision.

“The imagination always

does something other,

never what it is told.”

For me, planning what I’m going to write only works when the plan is provisional, conjectural, and I am ready at any moment to see that the plan was wrong and chuck it in the trash. All plans are proved wrong by the writing itself. As soon as I begin to write, what I actually write diverges from what I meant to write, what I dimly envisioned.

How do you balance content with form?

For me, the crucial formal element of fiction on which everything else hinges is the way that it’s narrated. If I can get the narrating voice of a story right in my mind’s ear, if I can be the source of that voice and write through it, the story can get told. All my novels are in first person (some with multiple narrators), so the narrating voice is coming from a character. I am writing from within this character, being the narrator-protagonist as I tell the story, and the story is the narrator’s story; in this way content and form merge.

Of course there are many other aspects of the shape of a novel that come under the heading of form, and for many people, content means theme. For me, all of that is subordinate to, or subsequent to, the reality of the story-world. I don’t think “I will write a book of a certain shape,” nor do I think, “I will write a book with a certain theme.” I believe a story starts from four essentials: a character, a place, a situation, and a narrating voice. When those are known, when those have attained rightness, then the story unfolds from within itself. Shape and theme are things that follow, that emerge; they do not determine the story.

How have your goals as a writer changed over time?

I think it has gradually come home to me how hard it is to say neither too much nor too little. I know it’s usually impossible to say what one means by hitting it head-on, but at the same time, I realize more and more that subtlety is not an end in itself, not necessarily a virtue.

Is there a quote about writing that motivates or inspires you?

There are many, but here’s something that has been posted on the bulletin board in my study for years. These are notes from a workshop given by the late poet Deborah Digges:

Art lives in: the bumbler, the unfit, the shadow.

The “I” must be violated, shattered, the distance must be broken—you are both the dreamer and the dreamed—you are acted upon by the world. The insistence that you must stay in control must be broken—the hope is that you will get lost.

You write from the unsocial, the anti-social, the sub-social—you write NOT for the culture’s approval—you leave even the reader behind, or risk leaving the reader behind, for the art.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

Don’t aspire to “be a writer”; if you’re a person who has to write, you will. When you’re about to fall asleep and a sentence comes to you that feels exactly right and you absolutely don’t want to get out of bed and write it down—get out of bed and write it down. Make a final decision that you’ll do that. That is the kind of commitment you need to make to your work at all other hours, as well. Do it, because you love it.

“Lose yourself in the work.”

Forget yourself in the work, lose yourself in the work. Be ruthless on behalf of the work, learn to say no to things that matter less than the writing. Find readers who will tell you what they really think—you can’t learn to write without readers. Don’t let your writing stand or fall on the question of whether you get published; don’t outsource your legitimacy as an artist to publishers. Learn to legitimize yourself in your own eyes, do whatever it takes, because you’ll need that to sustain you over the long term.

Learn some kind of meditation. Writing and meditation are very similar mind-disciplines.

Constantly ask, “Why not? Who says I can’t?” The limitations you place on yourself are the most constricting of all. You must create yourself creative. The first thing the imagination must create is itself.

What’s the best advice you’ve been given as a writer?

I think it might have been the advice, which I got from Kathryn Marshall, the author of My Sister Gone, that I should try writing my first attempted novel in the first person. Doing that taught me that I had to write from inside the character, made me learn how to do that, so that for the first time I was truly writing fiction.

Is there a question you find surprising that people ask you about your work?

What surprises me is that sometimes readers understand or react to a character in a way I never imagined when I was writing. The character I thought I knew inside and out becomes, in a reader’s mind, someone I don’t recognize—now that’s surprising.

What do you find most challenging about writing?

The hardest thing is being between projects, feeling like I have nothing to write, nothing to say that I haven’t heard myself say before, waiting for something to come and not knowing if it ever will.

When you’re not writing, what do you like to do?

Teach, cook, ride my bike, watch baseball, build carpentry projects. And read, of course.

About Lowry Pei

Lowry Pei’s first novel Family Resemblances was published in 1986 by Random House (Vintage Contemporary, 1988). His story “The Cold Room” appeared in Best American Short Stories 1984, and “Naked Women” appeared in The American Story: The Best of StoryQuarterly. He has published short stories, essays, memoirs, and criticism, and his book reviews have appeared in New York Times Book Review. His unique point of view owes much to his unlikely origins as the son of an engineer from Suzhou, China, and a schoolteacher from a small town in Kansas. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with his wife, and teaches writing at Simmons College.

[Toffoli, Marissa B. “Interview With Writer Lowry Pei.” Words With Writers (January 25, 2012), https://wordswithwriters.com/2012/01/25/lowry-pei/.%5D

[…] I instantly liked and was intrigued by this writing professor, Lowry Pei, who has since become mentor, colleague, and friend, and I thought I’d go along with it and […]