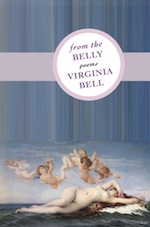

An introduction to Virginia Bell, author of the poetry collection From the Belly (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2012). Bell is a Senior Editor with RHINO Poetry and an adjunct professor at Loyola University Chicago, where she particularly enjoys teaching courses on Women in Literature, Early American Literature, and Nationalism and Literature. Her poems have been published in numerous journals and anthologies, and are forthcoming in Spoon River Poetry Review. Throughout 2013, her poems will be heard on WGLT’s Poetry Radio.

When asked about the title of her new book, Bell shared that it “allowed me to group seemingly disparate poems together: ekphrastic ones and ones about the body generally, as well as the ones about food or the mother’s body. I think I liked the idea, too, of the belly as gut, as the place where poems come from.” Indeed, her poems are a gutsy, unflinching exploration of what it means to grow up, to be a woman and a mother, to remember, to tell stories—to live.

Quick Facts on Virginia Bell

- From the Belly website

- Home: Evanston, Illinois

- Comfort food: pasta

- Top reads: Anne Carson (especially Autobiography of Red), Carmen Boullosa’s Son vacas, somos puercos, Linda Bierds’ The Profile Makers, Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, Marie Howe’s What the Living Do

- Current reads: Anne Carson’s Decreation, Ernesto Sabato’s El túnel, the poetry anthology The Open Door: 100 poems, 100 Years of Poetry Magazine, and The FSG Book of Twentieth Century Latin American Poetry

What are you working on at the moment?

I am working on some poems about a friend who recently survived breast cancer. I’ve written a few poems about her and our friendship during the past six months. I thought that she would hate me writing about her life, but she actually loves the poems, so that’s been neat—to write and share the poems with her.

The other thing I’m working on is moving beyond confessional poetry. I’ve been working on a series of poems based on the writings of Cabeza de Vaca. He was part of a multi-ship expedition to the Americas in the 16th Century and was shipwrecked off the coast of what’s now Florida. Cabeza de Vaca and the other three men that survived walked for eight years, through what’s now the southern US, before they found Spaniards again. He wrote an account of the experience, La Relación. I had to read his account in college, and I teach it now, but I’ve become interested in exploring a poetic reaction to it instead of a critical reaction. Two of the poems in this series will be in the next issue of Spoon River Poetry Review.

“I’m fascinated by historiography,

the writing of history.”

I’m fascinated by historiography, the writing of history, and it’s part of what I wrote my dissertation about years ago. I recently heard about Agnes Nestor, a labor leader in Chicago in early 20th Century. I found her autobiography in the stacks at Loyola University. No one had taken it out for decades; the spine was falling apart and crumbling. What’s interesting to me is how she represents herself by not representing herself. It’s supposed to be her autobiography, but she tells you almost nothing about her personal subjectivity. The book is more of a chronological list of her activism. I’m writing a series of poems that imagine her subjectivity and fill in the blanks of her autobiography.

Where did the idea for From the Belly come from? How did the book come together?

Let’s start with the title. It’s a phrase from the poem “Art History.” The poem is loosely based on an afternoon I spent walking around the art museum in Cleveland, Ohio with a college friend. You know how poems are—it’s sort of based on that afternoon, but it becomes its own fiction. This friend was an art major, and she still paints, but here we were walking around the museum, looking at all these famous paintings, by artists like the Impressionist masters, and for every painting we looked at she had something negative to say. She was being such a severe critic! The afternoon culminated with the two of us standing before one of Monet’s famous water lily paintings. She pointed to one tiny section in the middle (“the belly”) of the painting and said something like, “This is the part I like. If I were to hang this in my own house, I would cut out this rectangle and that’s the only part I would put on the wall.”

What interested me most was the violence of the idea of cutting out something from Monet’s lilies, but also the beauty of having that strong and irreverent an aesthetic opinion and desire. I’m answering your question with this story because I don’t want the word “belly” to mean only the literal belly that digests food, or the pregnant woman’s belly, although in some poems it definitely means these things. The title allowed me to group seemingly disparate poems together: ekphrastic ones and ones about the body generally, as well as the ones about food or the mother’s body. I think I liked the idea, too, of the belly as gut, as the place where poems come from.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

I feel like a beginner late in life, so this book was a learning experience for me. I recognize that many of the poems are narratives, or at least pieces of stories, and I just hope that some of the stories resonate with people, make them think about their own lives in some way that they hadn’t before. More specifically, I hope that some readers will think a little more about the experience of gender in the world—not just being a woman, but also being a boy or a man. There are a lot of poems about how gender frames our experience and how we think about gender, at least in my generation.

Where and when do you prefer to write?

I wish I had a better routine, that I were more disciplined. I write in my home office when my kids are at school on the days when I’m not teaching. I love to write in the morning because that’s when my head is most clear. Ideally, probably after exercising in some way; going for a run or a walk clears my head.

Where would you most want to live and write?

In a warmer climate than Chicago. Somewhere I could write outdoors, even though I always write indoors now. Barcelona in the spring and summertime, with an apartment with a view of the Mediterranean Sea and a little terrace. This is my fantasy. But, I actually am happy to write right where I am. I feel fortunate that I have space in my house where I can write, and time alone to work. Those are really the two most important things—space and uninterrupted time alone.

Do you listen to music while you work?

Sometimes, when I get started. Usually, once I get into a flow, the music starts to interfere so I turn it off. Even if it’s music without words. I think it’s the rhythm—if that starts to overtake the poem too much I have to turn it off.

Do you have a philosophy for how and why you write?

I write for a couple of reasons. One is that I always wanted to at earlier stages in my life and I didn’t let myself. When I was younger I think I always felt that I should be doing something more practical or career-driven. Even though what I was doing wasn’t all that practical, literary criticism just seemed more practical than writing poetry. It’s really just as arcane—there may be even fewer people who read literary criticism than read poetry.

“I write because I just think

too much about things.”

I write because I just think too much about things. If I don’t write them, I keep obsessively thinking about them. Exploring through writing, I can let certain things go. If I write enough about them, then they don’t occupy me as much. When I started letting myself write more, when my second child was a toddler, I really underestimated how pleasurable writing is. As difficult as it is, even if a poem doesn’t come out well, just trying to do it is a great way of spending time and being alive in the world.

When you’re stuck getting started on a poem, where do you look for inspiration?

Sometimes I put the poem away, for weeks, months, maybe even a year. For the Cabeza de Vaca poems, I started drafting them over a year ago and they weren’t working, so I put them away. I recently started working on them again and I realized that I needed to go back to the text that was inspiring me. I needed to reread the book, and that was enormously helpful. You think you remember everything, but you don’t.

The other thing I do is workshop poems. I ask people I trust to read them and give me feedback. There were a couple of poets I met in Washington, DC who were wonderful in this way. And when I moved to Chicago, I met more poets and moved in and out of writing groups, and I can’t imagine having written From the Belly without that process.

How do you balance content with form?

I don’t have an MFA, so when I started to take creative writing seriously, I had to teach myself. I would give myself the exercise of trying out forms. Most of the poems didn’t work out, but I learned a lot. The poem “No Words for These Matters” started out as a sestina, but I radically pared it down to make it work. The six words I had chosen for the sestina are still in it though.

A poet friend once told me that you need to keep playing with a poem for as long as you can before you consider it done. Even if you think it’s good the way it is. You should play with the form. Just try different kinds of lines and stanza breaks and you will see things emerge that you didn’t even realize were in the poem. I resisted that advice for a long time, but it’s so true.

How do images inform your work?

I’m going to interpret your question as an invitation to talk about ekphrastic poetry. I think I consciously started working with images because I always loved Sally Mann’s photography, even before I had children. I was fascinated by her work and the notion of being a photographer/mother and using your children as your subject. And then when I was writing poems about my own kids, it felt weird. I worried that I was misrepresenting them. But I picked up her book, and I could write about the relationship between parents and kids without having to write narrowly biographical poems about my own kids. And I love visual art—I have no training in it, no business writing about it, but I love it.

What’s the relationship between fact and fiction in your poetry?

“Memory is so fallible, so untrustworthy,

but in a beautiful way

because memory is imaginative.”

I think the key word to the relationship is memory. Memory is so fallible, so untrustworthy, but in a beautiful way because memory is imaginative. Many of the poems in the book seem to be about my childhood or my life, but fact changes into fiction from the get-go. I don’t really know if I remember things accurately, and I don’t really care. My memory has served as a kind of fiction machine.

There have been a few times when I’ve shown people a poem about an event they were a part of, and they were like, “That’s not what happened!” They remember it completely differently, and I think that’s fine.

Is there a quote about writing that motivates or inspires you?

Here are the two quotes from Dean Young in The Art of Recklessness:

“Let us forgive ourselves for writing poems that aren’t better than every other poem that has ever been written.”

On writing and revising: “It is and needs to be a messy process, a devotion to unpredictability, the papers blowing around the room as the wind comes in.”

What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

You have to be open to constructive criticism; don’t be afraid of it. Look at it as part of the fun, and keep working at your writing.

What do you find most challenging about writing?

Insisting that it deserves a place in my life, and carving out time and space to do it. Also, putting that hyper-critical voice to the side while you’re writing, but still being able to summon that other voice, which is not hyper-critical but careful. Being rigorous—paying attention to detail, and being willing to revise.

When you’re not writing, what do you like to do?

I love to hang out with my boys and my husband, have dinner, go to movies, do whatever families do. One of my sons taught me how to play the Japanese game Go this winter. My other son loves to practice his card tricks on everyone in the family these days. I love to travel. I love to walk and hike. I like to cook. I like to be in the classroom teaching. And, as a Senior Editor of RHINO Poetry, I like to read submissions.

About Virginia Bell

Virginia Bell’s poetry will be heard on WGLT’s Poetry Radio throughout 2013, and two of her Cabeza de Vaca poems are forthcoming in Spoon River Poetry Review. Her first collection of poetry, From the Belly, was released by Sibling Rivalry Press in 2012. Her poetry has also appeared in CALYX, a Journal of Art and Literature by Women, The Mom Egg, Poet Lore, Pebble Lake Review, Wicked Alice, Ekphrasis, Contrary Magazine, Woman Made Gallery’s Her Mark: a Journal of Art and Poetry, and Beltway Poetry Quarterly, as well as in the anthologies Brute Neighbors: Urban Nature Poetry, Prose and Photography and A Writers’ Congress: Chicago Poets on Barack Obama’s Inauguration. Bell has a PhD in Comparative Literature and has published articles on activist writers such as Eduardo Galeano and Leslie Marmon Silko, and also the Instructor’s Resource Manual for Beyond Borders: A Cultural Reader (Houghton Mifflin 2003). She is a Senior Editor with RHINO Poetry and an adjunct professor at Loyola University Chicago.

Buy From the Belly, preferably at your local independent bookstore.

[Toffoli, Marissa B. “Interview With Writer Virginia Bell.” Words With Writers (January 27, 2013), https://wordswithwriters.com/2013/01/27/virginia-bell.]

From the Belly by Virginia Bell (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2012).

[…] Sebastian (2011) Behm-Steinberg, Hugh (2010) Bell, Virginia (2013) Budbill, David (2012) Day, Lucille Lang (2014) Doyle, Caitlin (2011) Drewes, […]

Marrrrrrrrrisa, once again a great interview, on many levels, and I’m going to be grabbing me some of her verse right away. I have a follow up question, which I’d like to discuss with you via email, but though we’re connected on so many platforms, I don’t know if we have each others. I assume you’ll have it when I leave it below. Look forward to taking to you soon, and thanks for the great work. Mark